By Phoebe Ingraham Renda

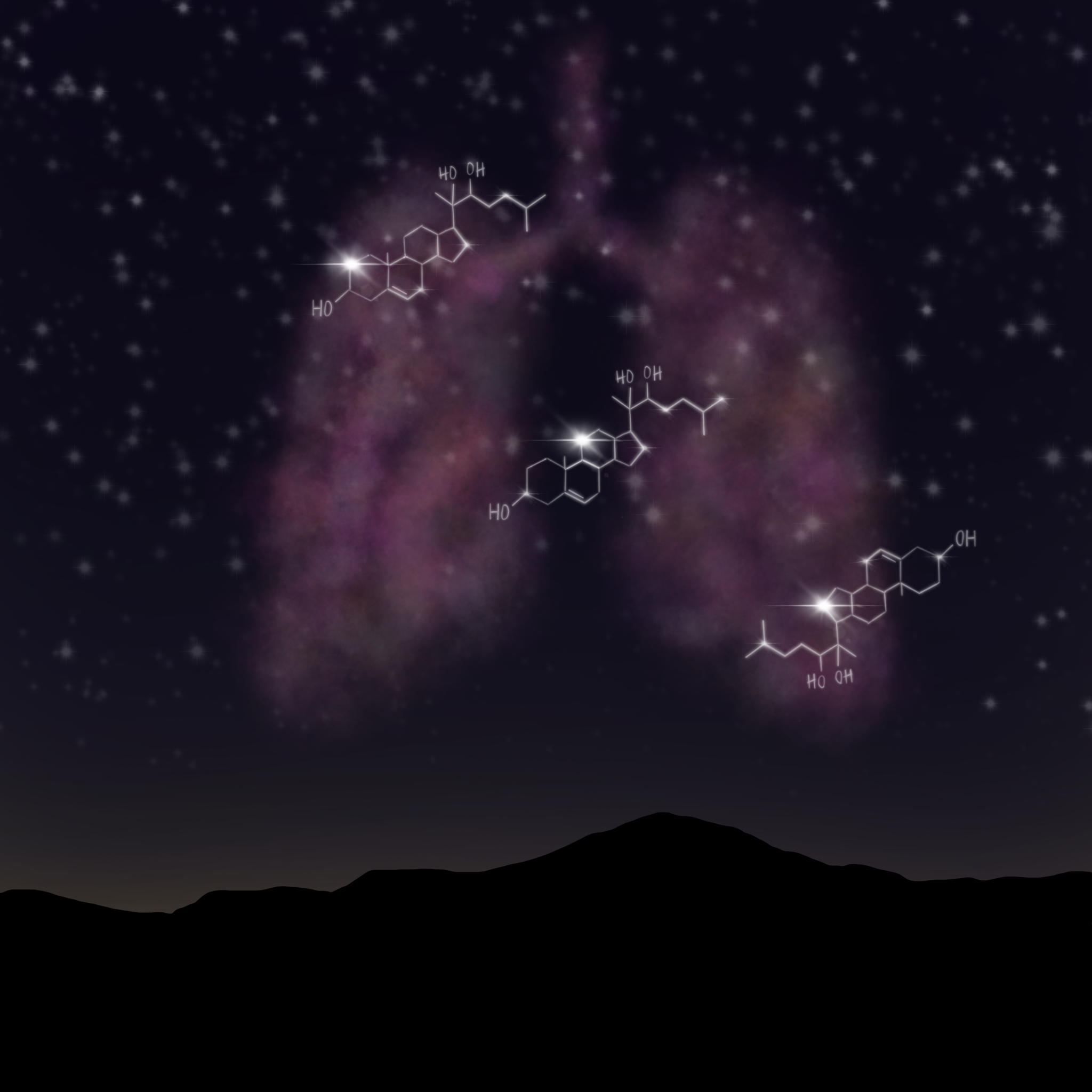

Across genetic, clinical and basic research, oxysterols reveal a key genetic-metabolic-inflammatory paradigm linking dysfunctional lysosomal biology with increased mortality from pulmonary hypertension. Illustrated by Phoebe Ingraham Renda.

Like little stomachs inside cells, lysosomes are organelles that use their acidic interior to break down cellular waste and debris. However, these acidic pouches also perform more nuanced functions, like cholesterol metabolism and sorting, cellular signaling and antigen presentation. As a result, dysfunctional lysosomes are associated with numerous diseases. Today, in a paper published in Science, University of Pittsburgh researcher Stephen Chan adds pulmonary arterial hypertension to the list.

The association between atherosclerosis (a chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall) and dysfunctional lysosomes piqued Chan’s research curiosity, as pulmonary arterial hypertension (a chronic lung disease caused by stiffening of the lungs’ blood vessels) also exhibits vascular inflammation.

“We have a very incomplete definition of how inflammation develops in the body to control disease processes,” says Chan, Vitalant Professor of Vascular Medicine in the Division of Cardiology, School of Medicine. “We know that inflammation is helpful in both health and disease, but we don't understand the molecular levers and tools that cells use to control it.”

In the study, lead author Lloyd Harvey, a 2023 graduate of Pitt’s Medical Scientist Training Program, Chan and colleagues found that lysosomal dysfunction is directly relevant to pulmonary arterial hypertension. When lysosomes are unable to make their interiors acidic, they lose the ability to metabolize and sort cholesterol. As a result, they begin to release oxysterols and bile acids, which are bioactive and inflammatory molecules. Additionally, the nuclear receptor coactivator 7 (NCOA7) protein, located in the membrane of lysosomes, directly regulates this acidification process—meaning it could have a role in orchestrating inflammation.

Using in vitro and in vivo models, the team discovered that when NCOA7 proteins were not active, or were absent entirely, lysosomes were unable to acidify themselves, lost the ability to metabolize cholesterols, and released inflammatory oxysterols and bile acids.

“We knew that lysosomes control inflammation, but we didn’t know how,” says Chan. “Our work uncovered that inflammation depends upon how cholesterol is sorted in the lysosome and how it is made into these oxidized forms—it’s a link that tells us a lot about how inflammation in the body develops and is controlled.”

From left to right, Chan, and Lloyd Harvey, 2023 University of Pittsburgh Medical Scientist Training Program graduate. Photo courtesy of Stephen Chan.

Serendipitously and in parallel with this basic science lysosomal research, Chan and collaborators in San Diego were conducting a clinical metabolomics study looking for blood metabolites that could predict patients with a high pulmonary arterial hypertension mortality risk. Using mass spectrometry, they looked at all the metabolites present in the bloodstream of more than 2,500 people with pulmonary arterial hypertension. In their analysis, the team found that several molecules were robustly associated with mortality; however, their structures were unknown.

“All we knew was that they had a molecular signature by mass spectrometry,” Chan notes. “We had to hunt for their identities.”

With help from chemical biologists and medicinal chemists, Chan and colleagues discovered that these mystery metabolites were oxysterols—the same inflammatory molecules identified in their NCOA7-lysosome research but not previously associated with disease severity.

Building on that finding and leveraging their population-level data, Chan and colleagues looked at all the different genetic versions, called alleles, of NCOA7 to see if any correlated with higher mortality risk. In that analysis, they found one associated allele—a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) where a G nucleotide was switched to a C, aptly named the C allele. In pulmonary arterial hypertension patients, individuals with only this C allele (CC genotype) had the highest risk for disease mortality.

Stephen Chan, Vitalant Professor of Vascular Medicine in the Division of Cardiology. Photo courtesy of Stephen Chan.

To prove the biological activity of this C allele, the team used cell models to assess if the SNP controlled NCOA7. They discovered that this C allele reduced the level of NCOA7 protein expression and that low NCOA7 abundance hindered lysosomal acidification—leading to oxysterol generation and, in turn, higher levels of inflammation.

“Being able to connect the population data with the molecular mechanism was an exciting turn of events that substantiated the importance of our work in human disease,” says Chan. “We were uncovering a pathway that, at least in part, is determining how likely and how quickly a person is going to die from pulmonary hypertension.” As a result, Chan notes, this SNP and these plasma oxysterols could serve as much-needed biomarkers to identify patients at risk for life-threatening disease.

Curious if the connection could be a therapeutic target, Chan teamed up with Ivet Bahar, a former Pitt computational biologist and current Louis and Beatrice Laufer Professor, Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Stony Brook University. Bahar used her artificial intelligence pipeline—which identifies small molecules that may act as inhibitors or activators of a protein—to identify candidate drugs targeting NCOA7. Using cell models to test the drug candidates, Chan and his team found that one candidate appeared to activate NCOA7. In a rodent model for pulmonary arterial hypertension, the drug activated NCOA7 expression and led to improvements in key inflammatory components driving disease.

Chan also predicts that this new genetic-metabolic-inflammatory paradigm could be relevant in treating other inflammatory conditions: "We believe this pathway has broad importance not just in pulmonary arterial hypertension but across many diseases, particularly in the aging population,” he says.