Illustration by Hannah Lesser

The data on Alzheimer’s disease in Black communities is stark: The risk is higher than average, but the rate of diagnosis is delayed.

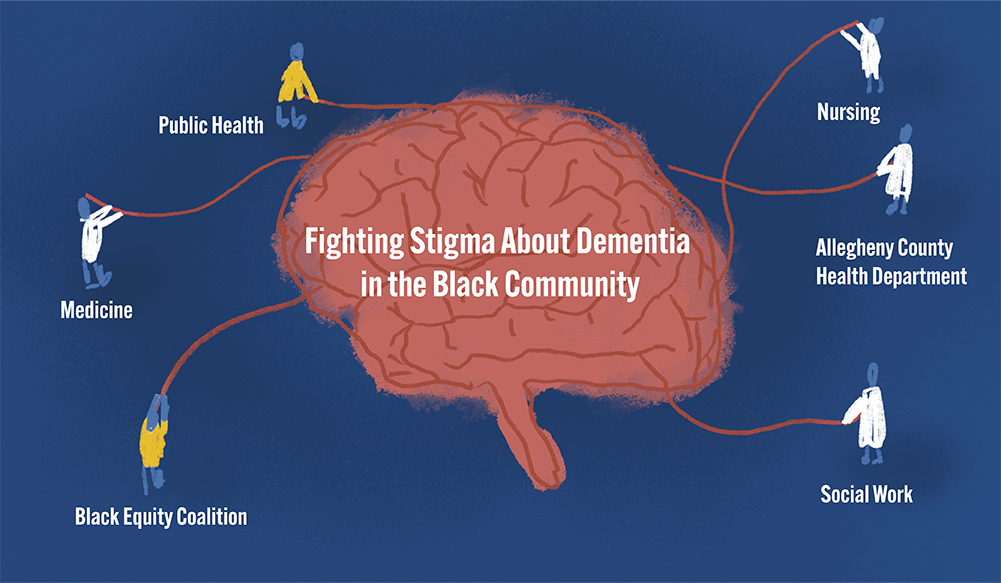

To address that, several University of Pittsburgh researchers from different departments are partnering with the Allegheny County Health Department and the Black Equity Coalition (BEC) in a new interdisciplinary effort.

The Brain and Cognitive Health Equity Campaign for Allegheny County through the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke pulls together leaders from the Schools of Nursing, of Medicine and of Public Health who will create counter-narratives about dementia that encourage early evaluation and intervention. The project also explores the use of blood-based biomarker testing for Alzheimer's diagnosis.

“The key here is that the field is undergoing some really significant changes,” said Jennifer Lingler, the principal investigator on the project, who is professor and vice chair for research, Department of Health and Community Systems, School of Nursing, as well as director of outreach, recruitment and engagement in the School of Medicine’s Alzheimer’s Disease Reseach Center.

“We've entered into an era of new therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease, where agents that are classified as disease modifying, meaning that they actually get at the underlying pathology of the disease, are now available,” Lingler said.

If populations with early diagnosis get the new treatments, Lingler said, “This gap is going to be further widened because people who are most at risk for the disease are going to end up being least likely to capitalize on these new opportunities.”

Others involved in the project are Dara Méndez, associate professor of epidemiology and associate director of the Center for Health Equity, and Elizabeth Shaaban, assistant professor of epidemiology, School of Public Health; Thomas Karikari, assistant professor of psychiatry, and Ann Cohen, associate professor of psychiatry, School of Medicine; and Kyaien Conner, Donald M. Henderson Professor, director of the Center on Race and Social Problems, and associate dean for justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion, School of Social Work.

Left to right: Lingler, Mendez, and Conner

Méndez helped pull the interdisciplinary team together on an unusually short timeline. “This is really a golden opportunity,” she said.

“I’m a huge proponent of ensuring that the work that we do is grounded in community experience, lived experience and voice,” Méndez said. “It's not enough for us in the academic space to come up with interventions and solutions because they won't be sustainable if it is not grounded in that experience in a community.”

Conner noted: “With the symptoms of early-stage Alzheimer's disease, stigma tends to be more profound, unfortunately, in communities of color, and tends to be a significant barrier to accessing care, particularly at early stages, when we know it can have the most meaningful impact. And so developing stigma-reduction interventions using culturally informed stories is something that is squarely in the niche of what social workers are doing every day in the community, trying to raise awareness and education and create some normalcy around our experiences, so that folks are not afraid to get help or to talk to others when they might be experiencing symptoms.”

Lingler said that discrimination and implicit bias in health care systems could contribute to an undervaluing of African American cognitive health, which could manifest in failure to screen or act upon complaints.

“All kinds of stereotypes are cued when you think about the possibility of Alzheimer's disease: Images of being incompetent, being labeled as crazy, having your independence taken away,” Lingler said. The grant seeks to address that through a public health messaging campaign to combat stigma around dementia in Black and African American communities in Allegheny County.

Trained interviewers will “elicit stories of experiences with dementia from community members and, then within those stories, try to identify counter-narratives, messaging that combats some of the stereotypes and can potentially chip away at some of the stigma,” she said. BEC will help the interviewers gain access to places where people live, work, play and age.

The health department will be key to disseminating the messaging campaign using a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant called BOLD, which stands for Building Our Largest Dementia infrastructure.

Conner said that conducting research in places like barbershops and YMCAs is essential.

“Expecting people of color to come to the ivory tower, to the university, to talk about brain health or to engage in some of the novel blood-based biomarker testing is a challenge,” she said. “We recognize that, although we have worked very hard to rebuild trust with communities of color, there’s a historical context there, and there are still many individuals who are not trusting. This project is powerful because it is bringing state-of-the-art science to the community and partners with them in the work.”

Karikari’s work on blood-based biomarker testing could also be a key element. “It is theoretically a very accessible form of testing that can be done in community settings and would bypass the systems that are problematic and are not working well,” Lingler said. “This would end up being a research test because this is a research-grade testing, and it's not something that's commercially available that you can even pay for if you wanted to.”